Advertisement

Author profile: Michael Kalanty, author of How to Bake Sourdough Bread

20 February 2025 · Author Profile

Michael Kalanty taught breadmaking for many years and has published two in depth educational texts on the fundamentals of bread baking. He recently worked with ckbk to release a new and updated edition of his second book, under the title How to Bake Sourdough Bread. We spoke to him about his baking and his books.

Q. Your first book, How to Bake Bread, introduced what is described on the cover as “a revolutionary system” for bread baking—can you explain what is revolutionary in your approach?

As a professional bread instructor, I always observed that so many books about bread baking were inconsistent from recipe to recipe, or showcased flamboyant results instead of actually delivering solid instructional material to the reader or student. I had also observed that people learn quicker and gain confidence faster when taught a standard set of skills that they can then independently transfer to similar products.

I was always inspired by the 19th century French Chef Antoine Carême who collected hundreds of sauce recipes from his chef colleagues throughout France. He grouped them into families and represented each group by what he termed a Mother Sauce. The idea was that once a chef made one of these mother sauces, they could easily make hundreds of variations from it. I wanted to use that same concept to structure my first book on bread.

I analysed my inventory of breads for the book according to Bakers Percentages (BP%), i.e. the weight of an ingredient divided by the weight of the flour. In a formula with 10 lb flour and 1 lb butter, the butter has a BP% of 10%.

How to Bake Bread, the author’s first book

Breads with less than 5% sweetener or fat are refered to as Lean Breads. They share commonalities of flour type, kneading times, proofing times, and baking temperatures. I chose Baguettes to represent this group and devoted one-fifth of my first book to each phase of making this renowned bread shape. Bagels, Dinner Rolls, Breadsticks, and Pretzels–these are all Lean Breads. Their shapes are different but their mixing, fermentation, proofing, and baking temps are all similar if not identical. If the student learned how to make Baguettes, making any of the other Lean Breads was similar. Just the shapes varied.

I grouped other popular breads using the same approach and created four more groups of breads that shared similarities in their formulas and in their procedures: Soft Breads, with respectable but not assertive amounts of sweeteners and fats; Rich Breads, with lots of butter and often with eggs; Slack Breads, with more water and baked into flat shapes; and Sweet Breads, packed with butter and sugar.

I named the groups The Five Families of Bread® and gave each one a Representative Bread. One-fifth of the instructional text on the book is dedicated to each one of them.

Structuring my book in this way made it possible for the student to focus on one family or more, depending on the class time available and length of the course. It also gave culinary instructors clear and precise guidelines for delivering discrete packages of learning to their students.

The invention of the Five Families of Bread® brought How To Bake Bread to the attention of the Gourmand cookbook awards, who brought the book into the spotlight at the Paris Cookbook Fair.

Q. How was How to Bake Bread received?

I was literally flabbergasted when the Director of the Gourmand Cookbook Awards contacted me about submitting How To Bake Bread for consideration at the Paris Cookbook Awards.

What followed was a whirlwind, with the book first being voted Best Bread Book in the United States. A month later I was sitting in the audience attending the Paris World Cookbook Awards with my book as one of three nominees in its global category.

When called to the stage to receive my engraved Swarovski Crystal award for Best Bread Book in the World, I delivered my humble thank you speech, in French, having asked the server at the cafe where’d I written the speech to check it for grammar. Standing on stage before an international audience of publishers, authors, and editors, I felt it a surreal moment I had never envisioned during my ime of working on the book.

The following day, the book was on display at the Paris Cookbook Fair along with all the other category winners. Agents shop for rights to these books and then translate and publish them for their respective countries. Here’s where I met Senac, a publisher from Brazil who created a Portuguese translation now used widely in professional bakery programs in that country.

A few months later, the book was adapted as the classroom text for several professional culinary and baking schools across the U.S., including The Art Institutes whose bakery programs across its many campuses put the book in the hands of a whole generation of young bakers.

What led you to write How to Bake Sourdough Bread as a followup?

The author’s sourdough title, now available in a new edition on ckbk

It wasn’t until How To Bake Bread went into its third reprinting that I began to work on the sourdough book. I was especially motivated by the feedback I’d received from students, home bakers, and culinary teachers applauding the approach of the first book. The concept of having one bread represent a category of similar breads had proven successful in bakeries and restaurants, bakery classrooms, and home kitchens.

The real decision was selecting a single bread to represent the category of sourdoughs as a whole. I was considering several types of different sourdough methods that I’d used both professionally and personally over the years and found that each had its own advantages. Yet no single one was broad enough in its application to speak for an entire category of breads.

I had been taught the Pain au Levain method by my French Master when I was a bakery apprentice. I’d been baking it for over three decades by the time I started writing How To Bake Sourdough. For several years, my students had been successfully baking it daily in our production kitchen at the California Culinary Academy and the Le Cordon Bleu schools. It’s reliability, its relevance to the category as a whole, and its signature aroma, flavor, and texture were all attributes that made this bread the only one I could have really considered to head up this category.

Q. Before writing your books you developed the artisan bread course at the California Culinary Academy? How did the experience of working with student bakers inform your writing?

The great thing about working with student bakers is that each one strives to do the very best, following the directions and executing the steps. At the end of class when all 18 baguettes are lined up side by side, you get to see just how much leeway a student can take and how what you thought was a straightforward directive could be interpreted in so many different ways.

This was the biggest blessing of working with students over the years. I learned to re-write my instructions with less room for error. The formulas themselves were revised and then revised again. Each time, the breads became more consistent across the bakery classroom.

My lectures became more focused, the more I taught. I observed how much information students were comfortable learning at one time. More importantly, I learned how much information was too much information. All of this helped me in structuring the book, in crafting the instructional pages, and in revising the formulas. I once overheard an instructor speaking to a colleague and saying something to the effect that “one thing you know for sure, the recipes in his book work!” That brought me a big smile.

Q. How to Bake Sourdough Bread is not a conventional cookbook in that is it far more than a list of recipes. It covers key principles, techniques, checklists, troubleshooting guides and tables of timings, temperatures and formulas. Why did you choose this structure?

This represents a large part of my philosophy as a teacher.

The structure is comparable to How to Bake Bread. This time, it introduces a sixth family—the family of sourdough breads. And the representative bread is the classic French Pain au Levain.

A full third of the book follows the process of making the Pain au Levain: Mixing, Development, Fermentation, Shaping, Proofing, and Baking. Including the step-by-step photographs of each phase of the dough, there are over 100 pages in the print edition dedicated to the process.

The collection of breads are all based on the same process so that once you have mastered the Pain au Levain, you will have confidence to take on any of the other breads. And you have a high probability of turning out a successful bread at the end. The same revolutionary system from my first book became the structure for my sourdough book. It was a system that had proven itself with the success of the first book.

Pumpernickel Sandwich Bread from How to Bake Sourdough Bread by Michael Kalanty

Apple Walnut Farmhouse Bread from How to Bake Sourdough Bread by Michael Kalanty

Rosemary Raisin Bread from How to Bake Sourdough Bread by Michael Kalanty

There’s plenty of opportunity for background reading while your sourdoughs are fermenting, slowly, overnight, in the refrigerator. I took advantage of that down time in the baking schedule to share a hefty dose of the information I’d learned from my own travels and baking with baker colleagues the world over. The book includes all the charts, scales, and tables that I had accumulated over my years of baking. It felt natural to share them with the reader.

What’s the best approach for someone new to the book? Should it be treated as a course and worked through from cover-to-cover? Or are there certain key sections to review before diving into making one of the sourdough bread recipes that is described? And what would be a good recipe to start with?

Let’s assume there are two categories of readers: One group that is completely new to baking sourdough breads. Another group that already has a sourdough starter and has had some degree of success with baking with it.

For the novice, start by simply making your own starter. The “Sourdough Starter—What is it?” section includes how all the information you need to do that plus, how to keep it alive. The entire process takes about 5-6 days to build a reliable starter—plenty of time for more reading.

Using the book as a self-guided learning experience, start with the section on “Baking with a Sourdough Yeast Culture”. This teaches you how to A. Make the Basic Levain and B. use that to make the Pain au Levain sourdough. Every step is explained in detail. Instructional photos visually summarize the whole procedure.

The Pain au Levain is the “Master Formula” for the book. It is the foundation of all the other breads in the collection of formulas. Best advice here is to make the Pain au Levain once, review the process, and then make the bread again. The intention is to internalize the steps, the sequence, and their purpose. Making the bread a third time should give you the confidence you need to advance to the collection of breads in the second half of the book. Each bread is based on the Pain au Levain’s process so no matter which bread you start with, you are reinforcing the skills you’ve already learned.

If you have your own sourdough starter and/or have baked sourdough breads before, you can temporarily skip the backstory about yeast, building starters, and maintaining them. There’s plenty of time for fermenting dough and proofing them and that’s perfect for diving into the technical aspects covered in the first part of the book.

But whatever your experience level, you should start with the “ Basic Levain (Method)” section. ALL the breads in this book are based on the Levain, so working your way through this step by step and actually making the Basic Levain formula prepares you for all the breads in the collection.

Nathan Myhrvold (creator of Modernist Cuisine and Modernist Bread) wrote the foreword to this book. How did you come to know Nathan? Do you share a common philosophy?

Nathan Myhrvold was the former Chief Technology Officer at Microsoft. He had just won his first James Beard Award for his magnum opus, Modernist Cuisine. Having always been fascinated by the countless number of breads one could make simply by combining flour, water, yeast, and salt in differing permutations, he’d set his sights on Bread for his second work.

Nathan approached me to come visit his Cooking Laboratory in Bellevue, WA. He invited me to work with the team of researchers and chefs that produced Modernist Cuisine, sharing with them the systematic approach of designing content and structuring a collection of breads.

Modernist Bread, the five-volume epic on the topic, created by Nathan Myhrvold’s team at Modernist Cuisine

We share a scientific approach to designing solid experiments and how observations of results can be distilled and tested so they can be replicated. He and I strongly believe that how information is shared is as important as the content itself. Nathan was a strong supporter of my work and I appreciate his inviting me to share his world at Modernist Cuisine’s Cooking Lab.

Why do you think sourdough and fermentation with wild yeasts has become so popular in the last few years? As a bread-maker, has your own focus shifted significantly in that direction, or do you continue to maintain a balance between conventional yeast breads and sourdough?

I routinely teach hands-on classes to novice bakers and I love guiding them through the sequence of phases that all conventional yeast breads follow. It’s terrifically satisfying to pass on centuries of tradition to a new generation.

My personal journey as a baker, though, leans heavily into the world of sourdoughs and wild yeast fermentation. The reasons are technical, sensorial, and nutritional.

Sourdough breads offer more variety in texture from soft and tender to al dente and chewy. The flavor profiles that fermentation brings to flour are akin to adding drops of secret flavor compounds to your doughs, ranging from vinegar sharpness to crisp apple tang. As your choice of flours broadens, your breads develop more complexity.

Sourdough breads are quite simply the most nutritious breads that you can eat. Energy from sourdough breads is longer-term. The reduced glycemic index of sourdoughs offers a much lower sugar spike than that of conventional supermarket breads. Sourdough supports pre- and probiotic microorganisms and medium-chain carbohydrates, the combination of which improve overall gut health.

What are some of the most common pitfalls and challenges when working with wild yeasts, and how does your book help sourdough bread bakers to avoid them?

I think that the sheer wealth of information about sourdough and wild yeast that can be found on the internet is simultaneously an asset and a pitfall for novice bakers. So much of the information contradicts, or is contradicted by, other information.

There is a Frequently Asked Question section in the book. The FAQs address the most common problems, questions, and scenarios that I’ve encountered myself or which have been presented to me by students and other bakers.

It’s a joyous part of the sourdough journey that a lot of these so-called pitfalls cannot and will not be avoided. That in itself is the art of learning how to bake. Encountering a challenge, researching the cause or remedy, and then learning from your own missteps. The FAQ in the first section of the book does exactly that: it explains why something is happening and shows you what to do about it.

It’s small failures that can make you a better baker. The FAQs are there to help you solve a problem. But they’re also there as teaching moments so you don’t find yourself back in the same situation.

Are there any unusual types of sourdough bread which you would encourage people to try baking? Perhaps something to convince a sourdough sceptic?

To develop your self-confidence, the gateway activity I recommend is practicing “discard baking”.

The first step to feeding your starter is to take half of it, more or less, and discard it. Fresh flour and water replace what’s been removed, and your starter is returned to its original weight. The portion you’ve removed is called the discard, because that’s what generally is done with it. But that’s only one possible action.

This discard is filled with flavor and beneficial microorganisms. Why not incorporate it into other foods you already bake or cook?

Griddle cakes/crumpets, scones, English muffins, or crêpes. Non-yeasted loaves like banana bread and gingerbread. Anything you bake that has chocolate, like cupcakes, devil’s food cake, or even chocolate chip cookies. All of these get amped up flavor from the addition of a small amount of sourdough starter.

Sourdough Pancakes from Slow Dough, Real Bread by Chris J L Young - s great use for sourdough discard

Not only will this practice make you comfortable with routinely feeding your starter, you’ll be training your palate to better appreciate the flavor notes you’ll find in abundance in your home-baked sourdough breads.

You include a recipe for sourdough pizza as a bonus at the end of the book? What are some of your favourite toppings for a sourdough pizza?

When I assemble toppings for a sourdough pie, my point of departure is the overall flavor profile of the eating experience. Sourdough brings an inherent lactic acid note. Think of Greek yogurt, sour cream, or buttermilk. The notes can be tangy or mild, but they share a low intensity of natural sweetness.

Counter-intuitively, you can use LESS cheese to top a sourdough pie. The lactic acid in the dough amplifies your cheese’s flavor intensity, giving you more cheese flavor.

That’s the strategy of the piled-high mushroom pizza at the end of the book. Instead of red sauce, I use a thin layer of a cream sauce made with a wine/vinegar reduction, spread over the dough. A much smaller amount of shredded mozzarella tops everything off.

For other topping ideas, think about vegetables that can be blanched first and piled over the cream sauce. Cruciferous vegetables like cauliflower and broccoli, in large forlets and with thick pieces of trimmed stems! These bering a slight sulphur note which balances the lactic note in the dough and the cream sauce.

Bigger pieces are always better than smaller pieces. You need more time to chew whole florets of broccoli. The texture of the sourdough crust aligns well with longer chewing and releases more flavor.

Is there an aspect of How To Bake Sourdough Bread that deserves more attention?

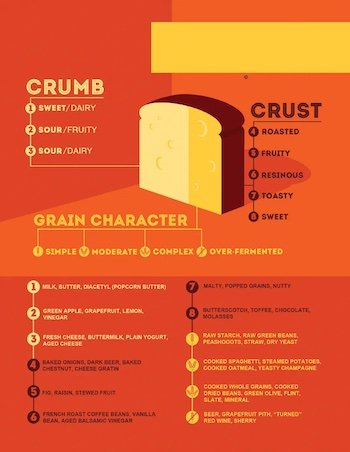

The Aroma & Flavor Notes for Bread chart gets less attention than I think it might, to be honest. Created along the lines of Ann Noble’s Wine Aroma Wheel and with the help of her guidance, the Bread Notes infographic identifies the primary aroma and flavor attributes of sourdough breads.

I developed it to help students better appreciate the breads they made in class and to give them tools to make informed choices for their future bread projects in terms of fermentation times, flour choices, and baking temperatures. The sensory characteristics of sourdough breads are wide and deep. Fermentation affects the level of sourness in the bread. It affect the type of sourness too, from creamy lactic to vinegary acetic notes.

The Maillard reaction that takes place during crust formation brings a virtually unlimited number of combinations of starches, amino acids, sugars, and flavor compounds into play for the baker. The part of the chart on Crust Aromas is al by itself a terrific topic of exploration. Crust notes can be Sweet, Toasty, Fruity, or Resinous. How the baker ferments a dough and what flour choices are made release a score of possibilities.

It's this sensory aspect of sourdough breads I think that sometimes gets short shrift. The book includes not only the Bread Notes chart but also several sidebars and discussions about how to coax different types of sourness from your breads. I use this chart with my bakery manufacturing clients when we do product development and it’s especially important when designing the Quality Assurance tests for manufacturers because they need to have consistency in their bakes day after day. This sensory chart is a valuable tool for anyone interested in developing their palate in general but especially for the serious bread baker.

The new edition of How to Bake Sourdough Bread is now available in full on ckbk. For full unlimited access, take out a 14 day free trial of ckbk Premium Membership.

Advertisement