Advertisement

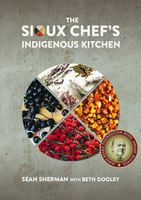

Prairies and Lakes

Appears in

By Sean Sherman

Published 2017

The day I turned seven, I got my first shotgun. It was a bright summer morning and I was sitting on the porch steps watching tractors bale alfalfa, a scent that’s burned into my memories of summer. I was home alone that morning when my grandfather pulled up in his old pickup, a late-1970s Chevy Cheyenne that was well ranch-worn and smelled of prairie grass and manure. He would have been in his seventies by then. He and his siblings were some of the first generation of students to go through cultural “Reformation” on the Pine Ridge Reservation. They were forced to attend Christian school and cut their hair, and they were forbidden from speaking their own language. All of my grandparents were fluent in Lakota, their first language. My grandfather’s father grew up on the plains with the Oglala, and when he was around eighteen years old he was in the Battle of the Little Bighorn (known as the Battle of the Greasy Grass by the Lakota). Shortly after that battle, and right after the massacre at Wounded Knee, most of the Lakota were rounded up and forced onto the Pine Ridge Agency. My grandfather and his wife had homesteaded a remote area within the Badlands of South Dakota, on the reservation, but during World War I the U.S. Air Force reclaimed their homeland for bombing practice by the newly formed Ellsworth Air Force Base near Rapid City. Great-Grandfather was forced to relocate to the ranch that remains in my family today.