Advertisement

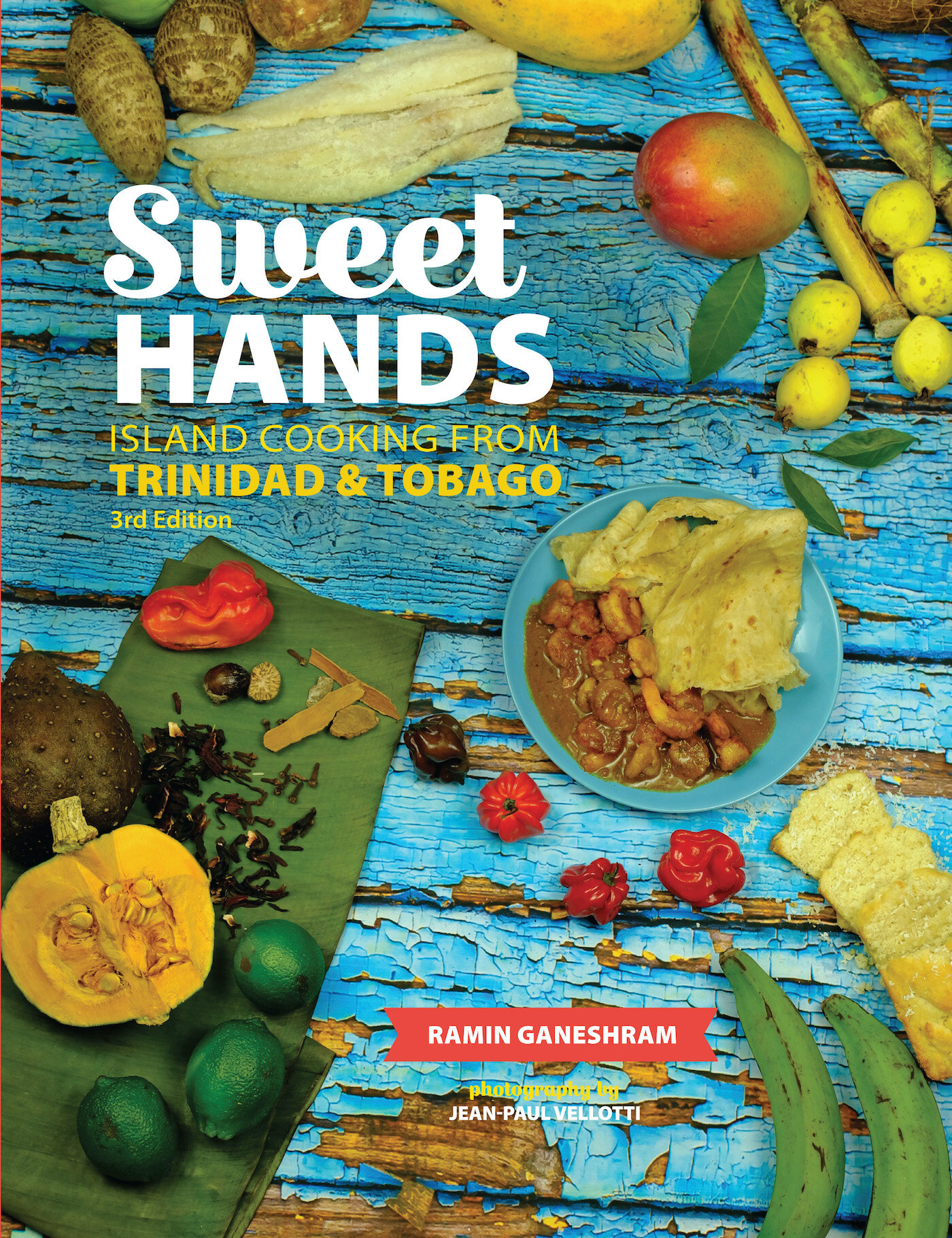

Behind the Cookbook: Ramin Ganeshram on Storytelling Through Food

2 March 2021 · Family Favorites · Regional cooking · Behind the Cookbook

Food is a gateway to human emotion, believes Ramin Ganeshram, the New York City-born journalist, historian, and author of Sweet Hands: Island Cooking from Trinidad & Tobago – new to ckbk, and an unbeatable source of island lore, traditions, and recipes. As a child, Ganeshram learned to cook “by osmosis” as her Trinidad-born father wove stories as he chopped, stirred and kneaded. As well as learning to cook, she learned the importance of food as a medium for telling ourselves and others about who we are, and where we come from.

For some years I was the chief food strategist for a market research firm. We used psychographic segmentation to advise Fortune 500 companies about how consumers were likely to behave toward their products. I examined why people ate certain things and when. Food history played a big part in understanding this. The futurist projections I made using these methods helped the world’s biggest food companies bring products to market and sell them successfully.

A social side benefit of this work was a ‘party trick’ that I used on new acquaintances: I’d ask them where they were from in the country or the world, and for a general description of their upbringing, as well as their parents’ professions and where said parents were originally from.

Using that information, my mind would whir through the catalog of disparate facts about regions, social class, and ethnic identity that I had gathered in my research. Then I would construct a fairly detailed story about what they ate on a regular basis and also on special occasions and holidays.

Nine times out of ten my tale would hit the mark, resonating with the listener who responded with awe and astonishment.

“Tell me how you eat…”

I was practicing the reverse of that famous line by 18th-century French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin: “Tell me how you eat and I will tell you who you are.” If people told me what they were, I would tell them what they ate, and in doing so tell them a story about themselves that was so irresistible they’d be on the edge of their seats, hungry for more.

But why should a simple story about weekday dinners of pot roast or pasta and weekend fish fries or fajitas, holiday tales of prime rib or chicken pelau be so compelling?

Because it was never really about the food at all.

Those who study food – from chefs to scientists, growers to gastronomes to anthropologists all know one thing: Food is a gateway to human emotion. All of the senses are engaged in producing, cooking and eating food: smell, touch, taste, sight and sound. Because of this, the act of eating – particularly certain meals – burns itself into our memory, for good or bad.

It is these memories, and the strong emotion that comes with them, that any good storyteller wishes to tap as a wellspring for their creativity. Since the memories of meals past (or present) are tightly interwoven with that emotion, food can become a rich medium from which to tell a story.

The connection: food and storytelling

This was something I realized in my Trinidadian father’s kitchen when I was very young – even before I had the words to understand the connection between food, emotion, and storytelling. All I knew was that if I managed to hang around while he was cooking, the stories would eventually come out, rising and falling in his rich baritone as, entranced by the tasks of slicing, chopping, stirring, kneading, and dredging, he slipped into the home accent of his island.

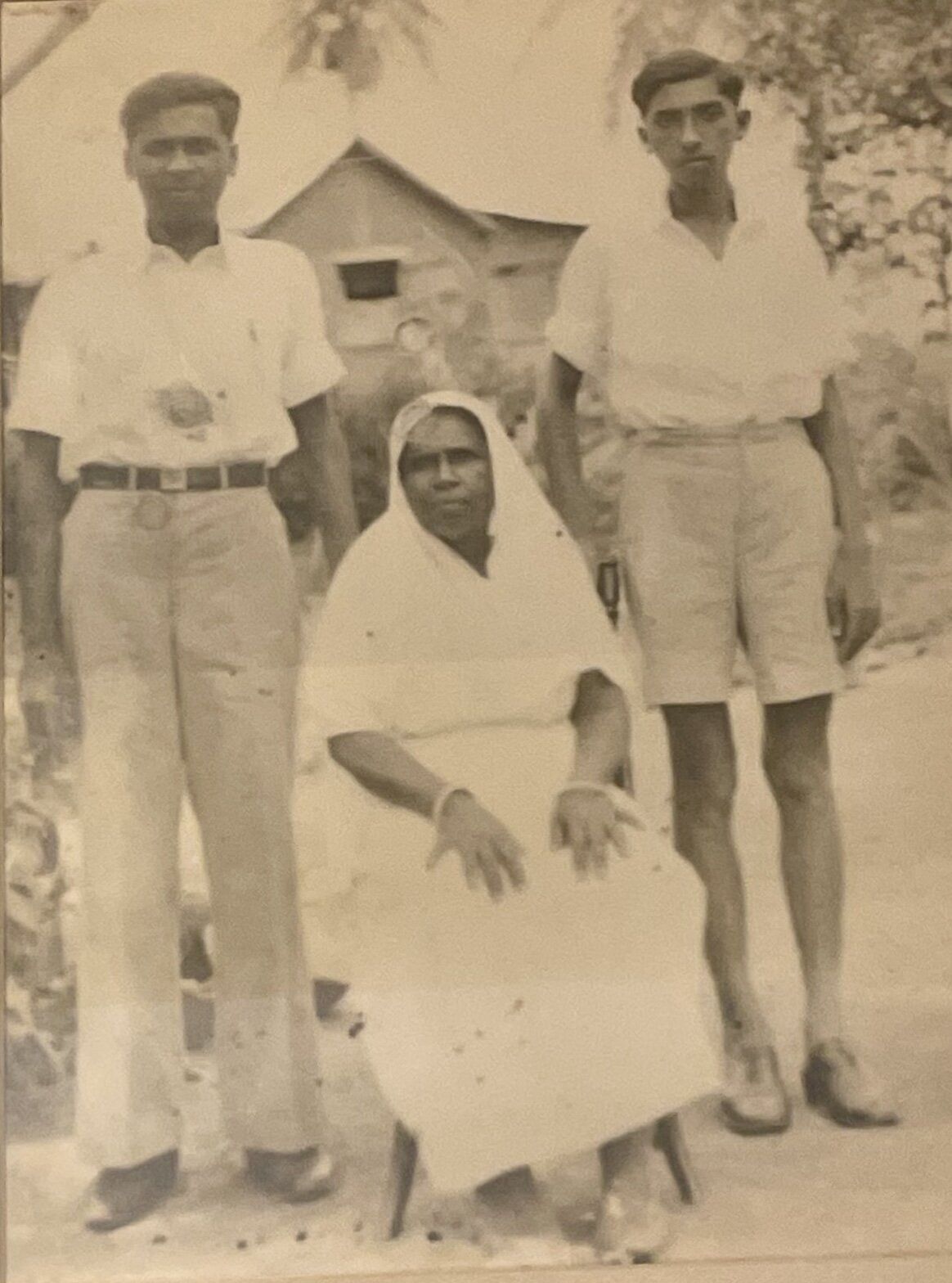

My father (right) as a teenager in Trinidad

At first it seemed that he didn’t even notice my small form, leaning against the counter or the wall next to the stove. I worked hard to stay quiet, lest the spell of his reverie break and he’d stop talking. As I got older he spoke directly to me, sharing the stories but also what they meant – along with the urgent reminder that these were stories I was meant to retell one day.

As he peeled potatoes he talked about his sister Toy, who could peel a root vegetable so finely, barely any flesh came away with the skin. This was a useful skill in a poor family that had to make every meal stretch.

While he massaged water into flour for roti, he spoke wistfully of his sister Mona who squatted by an open fire by the time she was just 8 years old, slapping the roti on the hot iron tawa while their mother worked in the public market, selling the clothes she had sewn for the sugar estate laborers from old gunny sacks. My father never managed to make roti as soft and delicate as Mona’s. “Meh han’ jus’ not set fuh it,” he’d say.

The fellowship of the table

Then there was the time he stood frying chicken in the cast iron fry pan and told me about the road trip he took across the American South in 1954 when he was newly arrived in the United States. Fried chicken was one of the first meals he was able to eat sitting properly at one of the few integrated diners he encountered after week upon soul-crushing week of ‘colored only’ water fountains, bathrooms, and restaurants.

It was a bewildering state of affairs for a man from a country where the majority of people were Black or Brown. Of all the indignities he endured, it was the denial of the fellowship of the table that stayed with him those many years later as he recalled too often eating a cold sandwich in the car while his white traveling companion could sit properly at a table and eat inside. His memory is now a story that I have retold a thousand times, one that comes back to me whenever I smell hot grease in a restaurant or in my own kitchen.

And all the while I listened to these stories, effortlessly and artfully told while he made his home food – a hard-won skill learned by trial and error – I learned to cook, without even realizing I was doing so. Even though my father didn’t actively teach me the skills of the kitchen, in the end I learned by osmosis because the techniques I watched became cemented in my mind with the stories he told.

Cooking as a keeper of culture

By the time I was a teenager I inherently understood that food could loosen the tongue of those who have otherwise learned to keep their stories and culture to themselves. I grew up in the 1970s in a continued era of American assimilation: Children were discouraged from learning the language of immigrant parents and families were encouraged to leave all of their ‘ethnic’ ways behind. In the end, all we had was the food that we could cook and eat behind closed doors, outside of the judgement and directives of larger society. Is it any wonder that so much was invested in the dishes upon the table? After all, we depended upon them to keep our culture whole.

Unlike my father, my mother, an Iranian immigrant, wasn’t much interested in food. She cooked out of necessity rather than desire. Only rarely did she seem to exhibit a longing or desire for the food of her youth, maybe because, unlike my father, it wasn’t something she was ever without. Instead, she embraced what she saw as the opportunity of America to remake herself into whatever she wished.

Even when we went to the Middle Eastern stores in Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue for some of the ingredients she needed for her cuisine, she never told me stories about the dishes she was going to make. As a result the language we used to describe her food didn’t evolve into a story but a pidgin dictionary of made-up words: kotlet, a patty of ground meat and potato became ‘Persian Patties’; halva was ‘Persian Peanut Butter’; pomegranates, called anar in Farsi, became ‘Arnolds’, a mispronunciation by my younger brother when he was a child.

The tales we tell

And yet, the tale I tell myself about who I am is most closely centered on a particular day in the kitchen of my mother’s father’s house in Kermanshah, Iran, a Kurdish city in the northwest from where my family hailed and where we visited in the summer of 1973. I was 5 years old, standing next to my seated father in the kitchen – or, more accurately a cookhouse; the kitchen was actually a small building inside a walled garden. There were fruit trees and a tiled pool filled with goldfish.

The cooking aromas wrapped themselves around us: The nutty smell of steamed basmati rice, vegetable-rich stews with chunks of lamb and plenty of saffron, the fresh clean smell of cucumbers being sliced for salad; the pungent astringency of tarragon, mint, and parsley laid out on a platter to eat out of hand.

In that redolent and marvelous place my little brother and I complained bitterly about the cousins who mocked us for being only half-Iranian and unable to speak Farsi. They never tired of asking their mother, a well-known television reporter, if we were stupid. When they were told that, no, we were just American, they thought ‘American’ and ‘stupid’ were two words that mean the same thing.

That was the first time I asked my father about this idea of Americans and Iranians and whatever it was my father was – because I noticed that, except for my grandfather, he was the darkest man there. It was the first time I noticed this about my father. He said he was from an island called Trinidad – and it was the first time I ever recall hearing of such a place.

It was then that my father explained that my brother and I are many things – Persian, Trinidadian, American. After considering this I announced confidently, “I am half Persian, half Trinidadian and all American!”

When my father laughed long and loud, I knew I’d said something pleasing. He had my mother translate for her father who smiled and patted my head. For the rest of the trip, my father delighted in that story – making me repeat my mantra until I tired of it, repeating it himself into my adulthood and up until his death.

Food: the story of who and how we are

Now, nearly 50 years later, when I crush saffron for rice the memory returns – a clear précis of the beginning of a sometimes murky lifelong journey to realize my own identity.

Whether we are food-obsessed or we eat just to live, food – choosing it, preparing it, and eating it – tells a story about who we are and how we are. The story is complex because its building blocks are many – culture, ethnicity, geography, education, social status, activity level, access to ingredients, religion, political beliefs, and more.

Sharing our dishes and our tables are a way to celebrate and to mourn, to express curiosity and to soothe the soul. Telling the story of a dish or an ingredient can be a stand-in for the stories of how a people rubbed along in the world through hardship and triumph. It can be an outlet for artistic creativity or self-control.

The food we eat and share gives us an opportunity to speak about our deepest emotions without saying a word.

Listening as my father cooked, I realized he was a gifted, natural storyteller. But he was a storyteller who believed himself without a medium – one whose stories unfolded like incense from a burning stick, redolent and all-encompassing only for a moment before they were gone.

But I know different. His medium was his recipes, and they still remain long after his death, each one a chapter in the long story of his life.

About the author

Ramin Ganeshram is a native New Yorker and an award-winning journalist educated at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. She is also a professionally trained chef and the author of numerous cookbooks. For eight years she worked as a feature writer/stringer for the New York Times and another eight years for Newsday as a feature writer and food columnist. She has received seven Society of Professional Journalists awards and an International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP) Cookbook Award for her work and has been a finalist for the IACP Bert Greene Award for Culinary Journalism.

A selection of Ramin’s favorite recipes from Sweet Hands

You can find every recipe from Sweet Hands: Island Cooking from Trinidad and Tobago on ckbk, in full.

Sign up for ckbk's weekly email newsletter

Related posts

Advertisement