Advertisement

Celebrate Lunar New Year 2026 with dumplings, noodles and more...

9 February 2026 · Holiday Menu

To welcome the Year of the Fire Horse, which begins on February 17, we’re diving chopsticks-first into the delicious traditions of Chinese New Year with Judi Rose, author of To Life!

By Judi Rose

Chinese New Year—also known as the Spring Festival or Lunar New Year—is a feast rich in symbolism. Jiǎozi, those plump dumplings shaped like ancient gold ingots, stand for wealth; a whole fish promises abundance (the Chinese word for fish, yú 鱼, sounds like yú 余, meaning surplus); longevity noodles guarantee a long life (no cutting allowed!); and sticky rice cake, nián gāo 年糕, ushers in growth and prosperity. Each dish tells a story—but the real magic happens when you make and eat them with people you love.

My own Chinese-cooking origin story began with a dumpling-making workshop, when my then six-year-old and I ducked out of a rainy Manhattan Sunday in search of something—anything—to do. Enter jiaozi (pronounced jow-tzuh): irresistibly moreish New Year dumplings that require mountains of chopped vegetables, nimble fingers, and a sense of humour. Surrounded by fellow first-timers, we filled, folded, and pleated with wildly varying degrees of success. The wonky ones earned the biggest laughs and sealed fast friendships with our tablemates, Chinese and American alike. Lesson learned: perfection is over-rated—connection is everything.

––––––

Making Chinese New Year dumplings is a labour of love and a time-honoured family ritual. Grandmothers, daughters, and children gather around the table in a well-oiled production line, turning out sixty to a hundred dumplings in one sitting. It sounds like a lot until you realise how quickly they disappear once the plates hit the table.

If you’re new to jiaozi, start small. Fold a couple of dozen with care and steam them until just right. Traditional fillings usually feature pork, but turkey thigh mince with a splash of dark soy sauce works beautifully for halal or kosher kitchens, while finely diced extra-firm tofu makes a satisfying vegan alternative. Unlike potstickers or gyoza, jiaozi are poached rather than steamed or fried, like this luscious version from My Street Food Kitchen by Jennifer Joyce. Jennifer’s recipe includes instructions for making your own wrappers, which is fun to do, but a pack of round “Northern-style dumpling wrappers,” available in Chinese supermarkets, are fine (but for the robust, hearty texture of authentic jiaozi, avoid “wonton” or potsticker” wrappers.”

Once I’d conquered dumplings, it was time to take on stir-frying—and the wok. Oddly enough, this essential piece of kit was missing from both my kitchen and my mother’s. That oversight has since been corrected… many times over. I now own close to 20 woks, each with its own personality: Cantonese, Northern style, round-bottomed, flat-bottomed, Indonesian—you name it.

In Chinese New Year cooking, the joyful sizzle of ingredients hitting hot oil is more than sensory pleasure—it’s symbolic. Tossing food high in the wok is said to bring good luck for the year ahead. With a little practice, you’ll find that a properly heated 35cm (14-inch) carbon-steel wok is light enough to toss one-handed, turning everyday ingredients into festival fare. A few golden rules: heat the wok before adding oil, cook hotter than you think you should, and never crowd the pan. If liquid starts pooling, you’re steaming—not stir-frying.

No Spring Festival spread in our house is complete without Kung Pao Chicken. Sweet, savoury, nutty, and just a little bit fiery, it’s the dish everyone hovers around. Crunchy peanuts, chilli warmth, and silky cubes of chicken—or tofu—make it an instant classic and an unapologetic crowd-pleaser.

Kung Pao loves company, especially garlicky greens flash-fried at the last minute. Pak choi and tender peppers bring freshness and a sense of renewal—just what you want at the start of a new year - like these vibrant Hong Kong-style Stir-Fried Greens with Garlic by Christine Wong.

For culinary drama, it’s hard to beat Clear Steamed Fish with Ginger and Spring Onions. I usually choose a whole sea bass and ask the fishmonger to fillet it while keeping the head and tail intact (not strictly traditional, but my compromise with fish bones). Gently steamed, then crowned at the table with sizzling ginger-scallion oil, it’s dinner and theatre in one. My trusted recipe comes from the wonderful—and much-missed—Yan Kit-So, whose books are well worth exploring on ckbk.

Longevity noodles are another non-negotiable. Slippery, golden, and tangled with beansprouts, ginger, and spring onion, they must remain gloriously uncut—snipping them is said to shorten life. Adults slurp enthusiastically; children need no encouragement whatsoever. Feeling adventurous? Jason Wang’s Xi’an Famous Foods includes a friendly recipe for making your own noodles from scratch.

If scratch-made noodles feel like a step too far, here’s an easy and delicious recipe using store-bought noodles by renowned Chinese-America food writer, Eileen Yin-Fei Lo. Her version includes scallops and oyster sauce, but shellfish-free cooks can just skip the scallops and use vegetarian “oyster” or mushroom sauce.

Stir-Fried Noodles with Steamed Dried Scallops from Mastering the Art of Chinese Cooking by Eileen Yin-Fei Lo

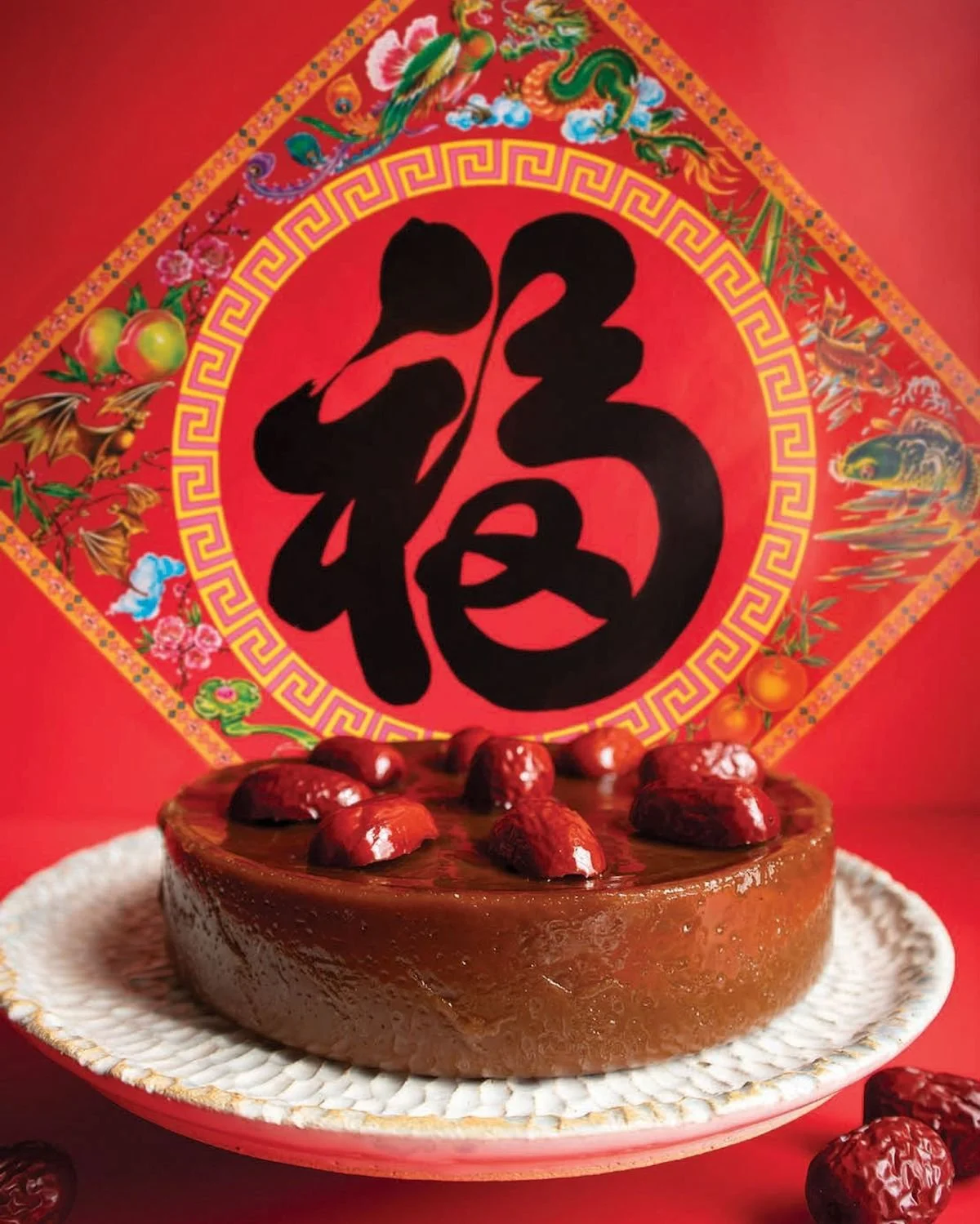

To finish, tāng yuán 汤圆—glutinous rice balls filled with sesame or peanut paste and floating in a lightly sweet broth—bring the meal full circle. Their round shape symbolises family togetherness. A cousin of mochi, they’re a little chewy, a little sweet, and a lot of fun to make. Yan Kit-So’s The Classic Food of China also includes an easy recipe for another traditional New Year dessert, nián gāo 年糕 (Year Cake).

If you’re avoiding sugar or refined carbs, a bowl of tangerines or satsumas makes a bright, juicy alternative. Their golden colour symbolises wealth, and their Mandarin name echoes the word for prosperity.

Tangyuan from Classic Food of China by Yan-Kit So

Year Cake (Nian Gao) from Vibrant Hong Kong Table by Christine Wong

Cooking for Chinese New Year isn’t about rigid perfection—it’s about rhythm, movement, and a bit of joyful chaos. The clang of wooden spoons, the whoosh of a wok, the perfume of garlic hitting hot oil—these are the moments that linger long after the plates are cleared.

Like Persian Nowruz, Jewish Rosh Hashanah, or Vietnamese Tết, the Spring Festival reminds us that the kitchen is where continuity lives. It’s where traditions are passed on, stories are told, and love is measured in shared meals. Whether it’s a child’s first triumphantly pleated dumpling, a teenager’s first Kung Pao Chicken, or steam rising from a sticky rice cake, this is a celebration of abundance, togetherness, and hope.

As we welcome the Year of the Fire Horse, may your table be full, your dumplings plentiful, and your laughter loud.

Explore more Lunar New Year favourites—from dim sum to desserts—in ckbk’s Lunar New Year Collection.

About the author

Judi Rose is a food writer, chef and cooking teaching and runs private cooking lessons for both kitchen novices and experienced cooks from her home in West London.

More from ckbk

Pastry chef Luciana Corrêa provides an overview of her favorite subject…

Dina Begum, author of the Brick Lane Cookbook, on why Bangladeshi cooking wouldn’t be the same without mustard oil

Roberta Muir speaks to the Australian chef and Thai cooking guru about his first cookbook, Classic Thai Cuisine

Advertisement