Advertisement

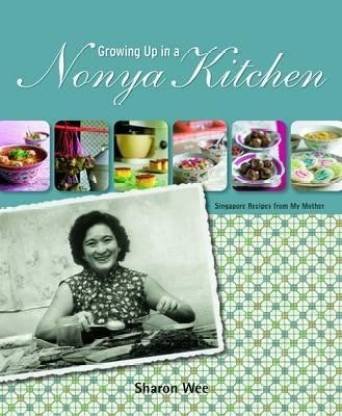

Author Profile: Q&A with Sharon Wee, author of Growing Up in a Nonya Kitchen

4 November 2021 · Author Profile · Family Favorites

“This cookbook tells my mother’s story”

Interview: Susan Low; photographs: Joshua Tan

Sharon Wee was born in Singapore and grew up in what she describes as a “very typical Peranakan family.” She left Singapore in 1992 to work in Hong Kong. Her career in marketing and advertising took her to Beijing, Shanghai and, in 1996, to New York City, where she completed an MBA and raised a family, and where she still lives.

Peranakan culture is known for its distinctive cuisine, and for the important role food plays in society – and Sharon has been instrumental in bringing that food culture to an international audience.

In her blog, Nonya Global, Wee delves into family history and contemporary life, and her book Growing Up in a Nonya Kitchen, which has has attracted much media attention in recent weeks. The book, which took Wee ten years to research and write, was written in memory of the author’s mother, whose recipes form the backbone of what is a deeply personal book

Sharon spoke to ckbk about her childhood memories of Singapore, explaining the intricacies of Peranakan food culture – and why she believes every recipe is worth saving.

Q: Tell me what it was like growing up in Singapore.

I come from a very typical Peranakan family in the sense that my eldest sister is 22 years older than me. There are six of us, and the one before me is 11 years older, and we are six girls. I lived in a typical Peranakan enclave: nice architecture, terraced houses. I remember in the 1970s my mum would go to the vendors and shops by trishaw.

Q: You are fifth-generation Peranakan on both sides. Can you explain a bit about Peranakan history and culture?

The term Peranakan pertains to a Chinese community in Southeast Asia, predominantly in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. The Chinese ancestors from my community came to Malaya in one of the earlier waves, before the 1900s. The settlers arrived in Malacca first, as far back as the 1500s or 1600s. It was then illegal to bring women over from China, so there is a strong theory that the men may have married the local women.

In Singapore, the Peranakans went to mission schools, and they worked with the British colonials as civil servants, they worked in the trading houses, and before the War, they built considerable wealth through rubber, shipping and, in my family’s case, opium. Peranakan women are known as Nonyas and the men as Babas.

They displayed their wealth in jewelry, architecture – and most of all in their cuisine. The cuisine is a testament to a leisured lifestyle. The women stayed at home and their identity was built around how their culinary were. Prospective mothers-in-law would come and judge their cooking.

Q: What did you learn about your mother’s life in the course of your research?

My mother actually did not learn to cook when she was young. Unfortunately, her mother died when she was in her teens. My mom’s education was disrupted by the War. She did speak English but not fluently, so I spoke Baba Patois with her, which is a smattering of Hokkien words with Malay.

My mom grew up in a wealthy household. They had a driver and a cook or two – so she did not learn to cook when she was young. She initially learned from my father’s side of the family as a rather young wife, I guess at 17. She learned from my father’s grandmother, who was blind but taught a lot of the girls in that neighborhood to cook.

The recipes were all committed to memory, because they didn’t know how to read or write that well. My mother had to cook for the entire extended family. It was very high-pressure. And she was also married to the eldest son, so she was under pressure to have children – and she kept popping out girls! But my father always said it was a blessing to have his six daughters.

Q: Does food play an important part in Peranakan culture?

Food was a big signifier of our identity. It differentiated us from the mainstream local Chinese population. It’s also a very good display of the amalgamation of the different cultures – you have the use of spices, you have chillies and coconut, which are used throughout Southeast Asia. But it also incorporates pork in dishes you would associate with Malay or other Muslim dishes.

And the eggs used in Peranakan desserts reflect the Portuguese colonial influence. There’s also the British influence and we observe the festival food of our Chinese ancestors, but with our own distinct preferences.

Q What are the best-known Peranakan dishes?

The signature dishes would be laksa and popiah, the spring rolls. If you go to a restaurant you would probably want what we call the Tok Panjang dishes – these are the ones that, in my family, we would serve on big occasions, such as Chinese New Year, weddings – and they would include dishes made with buah keluak, which is distinctive of Peranakan cuisine. I actually got caught by US Customs once, trying to bring some in!

Q: What specific recipes do you remember from growing up in Singapore?

A lot of it has to do with my mom’s cooking, and all the Chinese New Year dishes in my book. It wasn’t just the dishes, it was the whole production and the whole experience, all that labor of love that went into producing two or three days’ worth of food.

We had multiple dishes laid out on this long extendable table, which is very typical of Peranakan families. And the giant pots of soup that my mom would make, and all the Sunday gatherings my mom so lovingly put together. She’d cook Laksa or Popiah or Mee Siam and she also made desserts – Pulot Hitam or Tau Suan. So I associate those gatherings with the food.

Q: What advice would you give to people cooking Peranakan dishes the first time?

In all honesty, when you open any Peranakan cookbook, it is easy to feel daunted and think, How am I going to cook this? But the truth is, as my daughter always said when she was young, ‘Practice makes progress.’ The first time you make it, you don’t always get it right, but by the fifth time you make it you say, I can do this – and it doesn’t take the whole day. And it’s enjoyable! Here, with Thanksgiving coming up, some of us will spend a whole week baking pies – you can do the same thing with Peranakan food.

Q: Is there a specific dish you’d recommend?

Yes. I would suggest Satay Babi. It is interesting because it introduces you to a couple of things. It introduces you to the basic spices: lemongrass, there’s a little bit of belachan, the fermented shrimp paste, dried chilles, candlenuts as the thickener, coconut milk – and you learn to pound as well. This is how I learned to cook as well, from my great-aunt. She taught me to pound the ingredients in a particular sequence.

The other thing, if you’re not into spice is Pong Tauhu. It’s an opportunity for you to learn to julienne bamboo shoots finely. You can also cheat a little – if you don’t want to make the clear stock, I have often used a good quality readymade chicken stock and you still get the experience of that soup.

Q: What does this book mean to you?

It tells my mother’s story. I don’t think there are many women in this day and age who are like her. It’s a real passing generation. My mom was born in 1930. She was part of what they called ‘the greatest generation,’ the pre-War generation. I imagine how she lived, being compromised in her education and not being able to read the newspapers; and yet, because she loved cookbooks, this was my gift to her. I’m just sorry that she never got to see it.

Q: Are the recipes you’ve documented in danger of falling away?

Absolutely. My cookbook does not document fully the extent of what the Peranakans ate. We’re often associated with the grand-style dishes. People bypass the daily dishes we have – and that is a compendium in itself.

There are very rare recipes – there were some in my mom’s collection that even I didn’t recognize. The thing is, the younger generation associate Peranakan food with being too complicated. And, sadly, there is an overall consistency in the more common recipes such as laksa and Nonya dessert cakes. You have to find the nuances. Within the Peranakan community, every family had a different way of making them – they had their own little touch. So those ought to be documented for sure. Unless we are guardians of these recipes – yes, some of them will just disappear.

Q: Which food writers do you most admire?

I admire Nach Waxman, who started Kitchen Arts & Letters. He was an anthropologist by training, and I studied anthropology as well at university. I admire those who introduce me to their culture. I’m very inspired by cookbooks because they take me into a world that I don’t understand, or that I know very little about. I learn from them – history, geography, culture...

In terms of food writers, the ones I admire most: I love Raymond Blanc. I met him and he seemed like a very nice man. I like Mary Berry, who I watched on ‘The Great British Bake Off’ and I’ve seen Yotam Ottolenghi each time he comes to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York and he comes across as having such a gentle, unassuming demeanor. Which is endearing because, as food writers, you don’t know it all. You need humility.

Q: Is there a single cookbook you treasure the most?

Actually, it is The Joy of Cooking. I’ll explain why: I treat it as a rather thorough reference book, like the Oxford Dictionary. I may cook from other fancy cookbooks – I buy a book, I try a recipe here, a recipe there – but when I’m in doubt, or I don’t understand, I go to Joy for comparison and to cross-reference.

Q: Will you write another book?

If I write another book, I would probably want to do something not entirely Peranakan cooking.

But I am working on a 10th-anniversary edition of Nonya Kitchen for next year. It will be an update on new techniques or new findings. There is a lot more that I have learned along the way, so I would like to update it and make it a little bit more comprehensive.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

Popular recipes from Growing Up in a Nonya Kitchen

ckbk Premium Members have digital access the to full content of Growing Up in a Nonya Kitchen on ckbk, including every recipe and photograph. The book will also be reissued in print in December 2021 — pre-order your copy now.

Listen to Sharon Wee

Sharon is the latest guest to feature on Gilly Smiths’s Cooking the Books podcast - listen below.

Sign up for ckbk's weekly email newsletter

Read more about ckbk authors

Advertisement